Thank you! Your submission has been received!

Oops! Something went wrong while submitting the form.

The past three decades have been dominated by a cookie-cutter model of extractive urban development that has fuelled inequality, privatised public space, and hollowed out democratic control. Profit and private power have been placed before people and place. There is, though, a growing real-world alternative: Public-Common Partnerships (PCPs). The PCP model - a diverse institutional design for collective ownership - can play a foundational role in shaping a commons-led approach to development that unlocks shared abundance and ensures democratic community control of assets and the value generated through them.

Starting with individual assets or resources, the PCP model empowers communities to democratically determine the course of development by working in partnership with local authorities and relevant public bodies. Through two case studies, Union Street in Plymouth and Wards Corner in Haringey, London, this pamphlet - and accompanying report - shows that public-common partnerships are an economically viable institutional form for democratizing urban development and empowering local councils and communities.

Public-Common Partnerships (PCPs) are a radically democratic institutional model that moves beyond the simplistic binary of market and state. PCPs turn the failed approach of public-private partnerships on its head by proposing that, rather than procuring private investors to develop key infrastructure and urban landscapes, councils and other public bodies can and should work with communities to design, manage, and expand the commons.

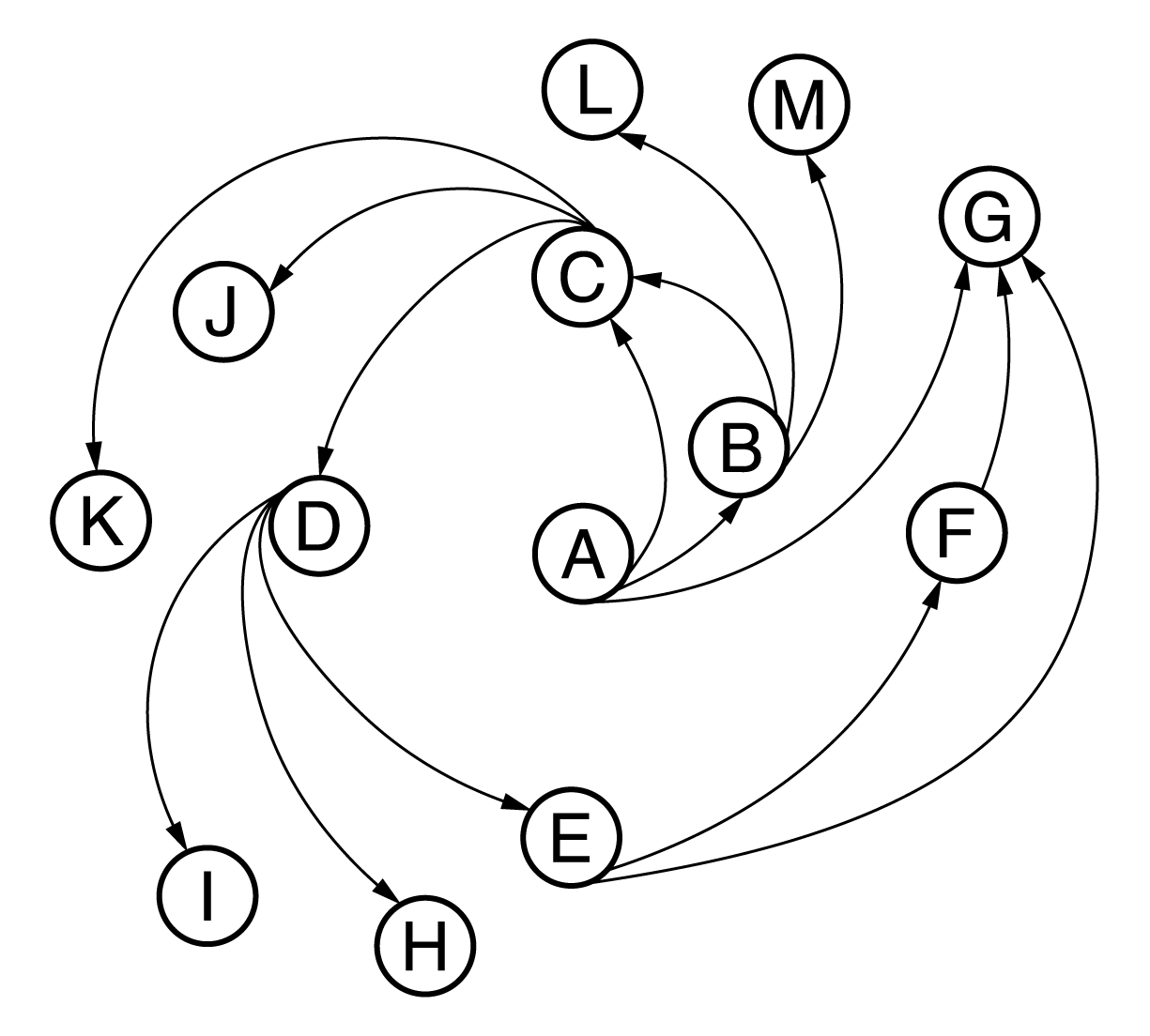

Our initial report described how PCPs require co-ownership and co-governance of an asset by three distinct but mutually supporting groups: 1) relevant state authorities such as council representatives or land-owning public bodies; 2) a ‘Common Association’ comprised of community members, residents, local business owners, and consumers; 3) project specific stakeholders such as union representatives and relevant experts.

From the perspective of public authorities, this governance model helps to mitigate political risk, addresses democratic deficits and reduces economic costs by enabling mutually supportive exchanges of finance, knowledge, and practice between PCP members. From the perspective of a Common Association, this model facilitates collectivised ownership and control over key assets and infrastructure, creating new spaces of commoning and democratising landscapes and economies.

"I want my kids, my grandchildren, to say ‘my grandmother started something different’. We were recognised, and now look at this beautiful place.”

The novelty of PCPs lies in their power to set in motion self-expanding circuits of radical democratic governance. Surpluses accrued through the profitable running of a PCP can be used to seed new PCPs elsewhere in a virtuous circle of commoning and democratic ownership. By serving as conduits for the commoning of towns and cities, PCPs do two things. First, they help public bodies and communities to bypass the disciplinary mechanisms of private finance that so often hinder democratic visions of the city and common ownership models. Second, their very existence gives lie to the idea that only private investors have the skills, power, and knowledge to develop our towns and cities. PCPs show that communities, working through common institutions, can and should be the ones making decisions about how their areas are shaped and reshaped.

The PCP approach works with an expansive understanding of economic democracy, moving beyond traditions of worker ownership and representation to explore the potential for wider democratic control of assets. They also confront limited understandings that exclusively equate ‘democracy’ with public institutions, instead demonstrating the opportunity and potential for new democratic spaces of urban development.

PCPs are place-specific interventions that speak to the needs of communities and local stakeholders, but we imagine many of the innovations presented here will be applicable to communities and local authorities elsewhere in the UK and beyond. The PCPs we outline in this pamphlet are proof of concept. They are evidence that local authorities no longer need to court private investors to ensure urban development. By implementing a PCP they can pursue a radically democratic alternative that expands the urban commons that rebuilds communities and puts them in control of where they live.

The PCP acts as the cutting edge of a wider project to socialise and commonise the way we process economic decisions. The aim is to produce a self-expansive circuit of the commons, bypassing the need for private financing and the disciplining mechanisms of finance capital, and changing how we as citizens relate to one another and the resources and infrastructure we rely upon. PCPs do this by incentivising an interlinking, self-expansive circuit of the commons in which the surplus of one PCP helps finance another, connecting groups on the level of ownership and governance structure. In this way, these islands of democracy can link up into chains of support, archipelagoes of democracy, before ultimately forming into a complete circuit of the commons.

Wards Corner sits at the busy intersection and underground station at Seven Sisters Junction in Tottenham, Haringey. Alongside numerous independent shops and terraced housing, Wards Corner is home to the ‘Latin Village’ indoor market, one of the last remaining hubs for the Latin American diaspora in London. Both the building and the land it sits on has been publicly owned since 1973. Since 2014, the market has been recognised as an Asset of Community Value by Haringey Council.

Following the collapse of the developer Grainger’s proposed redevelopment of the area in August 2021, a plan that typified the extractive model of urban development and was opposed by local residents and businesses, the path is clear for the delivery of a Community Plan via a ‘Public-Common Partnership approach’.

The purpose of a PCP for Wards Corner is to establish the Wards Corner building as a community controlled asset that will function as the motor of a wider democratic revitalisation of the surrounding area. The model embodies the principle that community led must also mean community owned, and that meaningful partnerships between public bodies and communities cannot be built on ‘dialogue’ alone. Furthermore, it recognises that ‘the community’ is not a predetermined object, but rather something constantly built and enacted through the creation of spaces of democratic debate. The Wards Corner PCP is not just about the governance of an asset, it’s a strategy for creating and strengthening relationships embedded in the long-term development of the area.

At the core of the Public-Common Partnership is the Wards Corner Community Benefit Society (BenCom). Introduced in the 2014 Co-operative and Community Benefit Societies Act, a BenCom is a business model where all profits must demonstrably be used for community benefit. Acting as a deliberative space engaging multiple different interests, the Wards Corner BenCom provides a democratic forum for governing the development of the Wards Corner site. The Wards Corner PCP provides an innovative approach to financing the redevelopment of the Wards building, with a forecasted cost of £11.7 million. Working with the housing and property consultancy Altair, the community plan developed a series of cash flow models, modelling how this cost could be met through a mix of community investment, grant funding and ethical investment.

If the BenCom acts as the ‘joint enterprise’, it is the Development Trust that fulfils the crucial role of the ‘common association’ in the PCP. The Wards Corner development provides a geographical focus for the cultivation of overlapping communities of interest, some tied to the process through physical proximity (community member shares) and others through value-based commitment (investor members identified through the community share offer). It is this community of interest that provides the critical mass from which the Develop Trust can begin to implement direct participatory processes of urban development. Through their efforts, the community is transforming the future of Wards Corner and putting the PCP model at the heart of democratic urban development.

An alternative, bottom-up model for the development of Union Street in the Stonehouse district of Plymouth began to emerge in 2016, following decades of failed extractive urban development models, when a community group called Stonehouse Action bought 96 Union Street, and developed it into a community centre. Stonehouse Action established Nudge Community Builders which is a community benefit society (BenCom). Their stated aim is to turn Union Street into the “first street in the country with more than 50% of buildings being community owned and 75% of businesses being social enterprises or purpose led businesses – a national example of what a future high street can achieve”.

To help deliver this vision, Nudge have explored using a land bank based on a Public-Common Partnership that would aim not just to build and retain wealth within a community while avoiding its displacement but also to capture some of the increase in wealth, using it to trigger a self-expansive dynamic of common ownership in which the income from one asset can support the purchase of new buildings. This form of democratised common ownership of assets prevents the benefits of development falling to landowners who ‘sit’ on their assets, securing a wealth windfall as the value of land rises, but without developing the area. It alsoIt also also helps inoculate the community against the extraction of wealth through rentier business models more generally.

Public-common partnerships put common associations, rather than private developers and speculators, in control of assets, resources, and planning. Our case studies have looked at how they can operate in urban contexts, focusing on the common, democratic, administration of land and property in urban environments. However, PCPs could also be used to govern a diverse range of assets, from rural projects such as county farms, to municipal energy and water companies. Their potential is barely tapped. One, two, many PCPs can flourish in the years ahead.

As the PCP model develops and expands, allowing more and more areas of life to be brought into common, democratic ownership and control, five lessons can inform the next evolution of the model: